前言¶ nsenter 是一个可以用来进入到目标程序说在 namespace 中运行命令的工具,一般可以用于在容器外 debug 容器中运行的程序。简单记录一下 nsenter 的常用用法。 常用参数¶ 最常用的参数组合是: # 有的版本不一定有 -a 这个参数 nsenter -a -t nsenter -m -u -i -n -p -t 参数的含义如下. Using nsenter, we will be able to run an arbitrary command within the context (technically: the namespaces) of our container, but without the associated security restrictions. Needless to say, this can be done only with root access on the Docker host. The simplest way to install nsenter and its associated docker-enter script is to run. Docker is an important part of many people’s environments and tooling. Sometimes, Docker feels a bit like magic by solving issues in a very smart way without telling the user how things are done behind the scenes. Still, Docker is a regular tool that stores its heavy parts in locations that can be opened and changed.

- Nsenter Docker Namespace

- Docker Nsenter File

- Nsenter Docker Pid

- Docker Nsenter Tcpdump

- Docker Nsenter Tutorial

It has been asked on #docker-dev recently if it was possibleto attach a volume to a container after it was started.At first, I thought it would be difficult, because of howthe mnt namespace works. Then I thought better :-)

TL,DR

To attach a volume into a running container, we are going to:

- use nsenter to mount the whole filesystem containing thisvolume on a temporary mountpoint;

- create a bind mount from the specific directory that wewant to use as the volume, to the right location of this volume;

- umount the temporary mountpoint.

It’s that simple, really.

Preliminary warning

In the examples below, I deliberately included the $ signto indicate the shell prompt and help to make the differencebetween what you’re supposed to type, and what the machineis supposed to answer. There are some multi-line commands,with > continuation characters. I am aware that it makesthe examples really painful to copy-paste. If you want tocopy-paste code, look at the sample script at the end of thispost!

Step by step

In the following example, I assume that I started a simplecontainer named charlie, with the following command:

I also assume that I want to mount the host directory/home/jpetazzo/Work/DOCKER/docker to /src in my container.

Let’s do this!

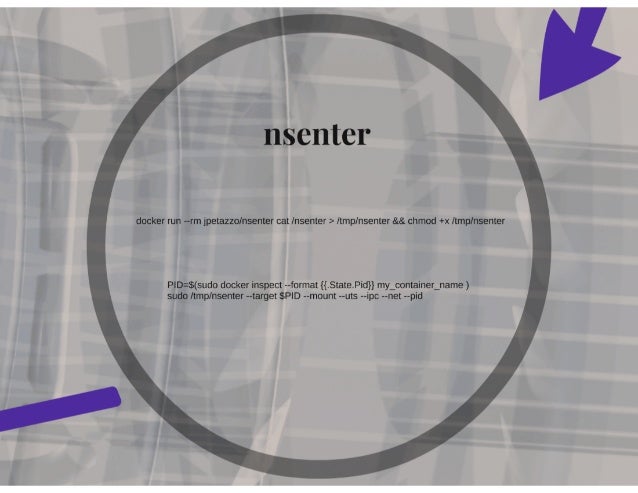

nsenter

First, you will need nsenter, with the docker-enterhelper script. Why? Because we are going to mount filesystemsfrom within our container, and for security reasons, ourcontainer is not allowed to do that. Using nsenter, wewill be able to run an arbitrary command within the context(technically: the namespaces) of our container, but withoutthe associated security restrictions. Needless to say, thiscan be done only with root access on the Docker host.

The simplest way to install nsenter and its associateddocker-enter script is to run:

Matlab 32 bit free download crack. For more details, check the nsenter project page.

Find our filesystem

We want to mount the filesystem containing our host directory(/home/jpetazzo/Work/DOCKER/docker) in the container.

We have to find on which filesystem this directory is located.

First, we will canonicalize (or dereference) the file, justin case it is a symbolic link - or its path contains anysymbolic link:

A-ha, it is indeed a symlink! Let’s put that in an environmentvariable to make our life easier:

Then, we need to find which filesystem contains that path.We will use an unexpected tool for that, df:

Let’s use the -P flag (to force POSIX format, just incase you have an exotic df, or someone runs that on Solarisor BSD when those systems will get Docker too) and put theresult into a variable as well:

Find the device (and sub-root) of our filesystem

Now, in a world without bind mounts or BTRFS subvolumes,we would just have to look into /proc/mounts to find outthe device corresponding to the /home/jpetazzo filesystem,and we would be golden. But on my system, /home/jpetazzois a subvolume on a BTRFS pool. To get subvolume information(or bind mount information), we will check /proc/self/mountinfo.

If you had never heard about mountinfo, check proc.txtin the kernel docs, and be enlightened :-)

So, first, let’s retrieve the device of our filesystem:

Next, retrieve the sub-root (i.e. the path of the mountedfilesystem, within the global filesystem living in thisdevice):

Perfect. Now we know that we will need to mount /dev/sda2,and inside that filesystem, go to /jpetazzo, and from there,to the remaining path to our file (in our example,/go/src/github.com/docker/docker).

Let’s compute this remaining path, by the way:

Note: this works as long as there are no , in the path.If you have an idea to make that work regardless of thefunky characters that might be in the path, let me know!(I shall invoke the Shell Triad to the rescue: jessie,soulshake, tianon?)

The last thing that we need to do before diving into thecontainer, is to resolve the major and minor device numbersfor this block device. stat will do it for us: Trials in tainted space money.

Note that those numbers are in hexadecimal, and later, we willneed them in decimal. Here is a hackish way to convert themeasily:

Putting it all together

There is one last subtle hack. For reasons that are beyond myunderstanding, some filesystems (including BTRFS) will updatethe device field in /proc/mounts when you mount them multipletimes. In other words, if we create a temporary block devicenamed /tmpblkdev in our container, and use that to mount ourfilesystem, then now our filesystem (in the host!) will appear as/tmpblkdev instead of e.g. /dev/sda2. This sounds like alittle detail, but in fact, it will screw up all future attemptsto resolve the filesystem block device.

Long story short: we have to make sure that the block device nodein the container is located at the same path than its counterparton the host.

Nsenter Docker Namespace

Let’s do this:

Create a temporary mount point, and mount the filesystem:

Make sure that the volume mount point exists, and bind mountthe volume on it:

Cleanup after ourselves:

(We don’t clean up the device node. We could be extra fancyand detect whether the device existed in the first place, butthis is already pretty complex as it is right now!)

Voilà!

Automating the hell out of it

This little snippet is almost copy-paste ready.

Status and limitations

This will not work on filesystems which are not based on block devices.

It will only work if /proc/mounts correctly lists the block devicenode (which, as we saw above, is not necessarily true).

Also, I only tested this on my local environment; I didn’t even tryon a cloud instance or anything like that, but I would love to knowif it works there or not!

Problem: How can you get a shell to your Docker container using nsenter?

Solution: The tool “nsenter” allows you to enter into Name Spaces. Container Namespaces are not an exception. Let’s see how you can enter Docker Container using nsenter.

nsenter Installation

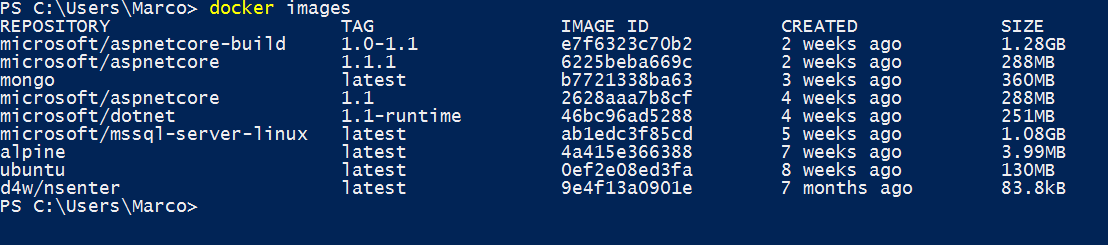

Docker Nsenter File

sudo docker run –rm -v /usr/local/bin:/target jpetazzo/nsenter

nsenter in action

Let’s say that I have a container “myapache2test” running. Sri satyanarayana pooja telugu pdf.

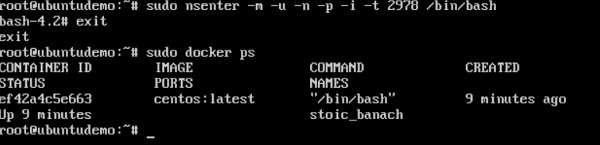

Step 1: Get PID of your container.

sudo docker inspect –format=”{{.State.Pid}}” myapache2test

When you execute the above command, you will get PID for the container “myapache2test”. i.e. 27576

Step 2: Use the PID to enter to the container. The command might look like similar to the one mentioned below (using PID in step 1: 27576)

sudo nsenter –target 27576 –mount –uts –ipc –net –pid

Nsenter Docker Pid

Bingo!!! You will get a /bin/bash shell into the container.

Shortcut: docker-enter

If you really wan to execute above steps in a single command, you can use docker-enter. Here you go.

Let’s say you have to enter your Docker container “myapache2test” running. You can use a command similar to the one below.

kd@DockerTutorials (Sun Jan 18 – 04:30:04) :~$ sudo docker-enter myapache2test

root@02bb749c90be:/#

You got a bash shell inside your running Docker Container. Enjoy!

I hope you enjoyed it!

Docker Nsenter Tcpdump

Thank you so much for checking it out!

KD

Docker Nsenter Tutorial

References:

https://github.com/jpetazzo/nsenter

http://blog.docker.com/2014/06/why-you-dont-need-to-run-sshd-in-docker/

http://blog.dotcloud.com/under-the-hood-linux-kernels-on-dotcloud-part